Also in the news...

Paul Beare Wins IR Global Member Of The Year

Paul Beare has been named Member of the Year at this year’s IR Global Conference in Amsterdam.

The Biggest Problem With Running A UK Payroll

We explore the biggest problem with running a UK payroll, together with the required functions of payroll calculations and net salary.

Taking It For Granted: How The UK Government Helps Growing Firms

In the UK, a number of government agencies offer a range of grants to help smaller firms to grow and prosper. The grants are typically designed to support innovation, encourage job creation, and underpin growth. In the last few years, a number of new initiatives have emerged, including grants aimed at boosting green technology and digital transformation.

Start-ups Wasting Over 2 Weeks And £37 Billion A Year On Admin

UK start-ups and microbusinesses are wasting over two working weeks every year on admin tasks, including managing mobile phone contracts, choosing energy providers, and buying insurance – according to new research.

The Costs For International Businesses Employing In The UK

In an ever-globalising business landscape, expanding operations to the United Kingdom can be a strategic move for international companies seeking new opportunities.

IP Tax Planning In The Age Of Anti-Tax Avoidance Intellectual Property (IP)

Intellectual property (IP) is increasingly the catapult to wealth creation in this age of innovation and globalisation. The World Economic Forum named innovative IP has estimated at least 75 industries are highly dependent on IP creation for further growth.

At the same time, global business models entice multinational corporations (MNCs) to strategically place their profitable IP rights in low-tax locations as a means to reduce overall tax rates.

However, since the 2008 financial crisis, cash-hungry nations have been hunting for additional revenue and a principal target has been so called ‘corporate tax avoidance’ on the part of MNCs that do not pay their ‘fair share’.

Taxation of these IP rights is increasingly a target of tax authorities, by means of audits, transfer-pricing challenges, and a push to fundamentally reform how IP profits are taxed in the global economy. The OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) initiative is the tip of this spear.

BEPS

Base Erosion And Profit Shifting

Pursuant to the BEPS initiative, the OECD has called for ‘new international standards’ for international taxation. Much of its agenda focuses on the international taxation of IP profits. For starters, the BEPS initiative accuses MNCs of causing distortions in the global economy by abusive planning that result in non-taxation of corporate profits, and states that transfer-pricing rules must be improved to combat this, including those related to IP profit shifting.

The initiative specifically advocates additional substance and transparency rules in order to benefit from any preferential regimes (including IP tax regimes) and linking the taxation of IP-related profits to where IP is created.

The BEPS initiative is a manifestation of global discontent and concern among nations that IP profits are not sufficiently taxed – though how a group of 34 nations with competing tax-policy objectives will be able to agree on new international tax standards is far from clear.

Regardless of the BEPS initiative’s outcome, IP tax planning continues to receive an unprecedented amount of attention. Notable examples include the public hearings of several prominent high-tech companies in regards to their tax planning, such as Apple before the US Congress or Starbucks and Google before the UK Parliament.

Further, many countries are already ramping up the rules for IP taxation rights, with an increased focus on economic substance. This approach generally requires that economics or business must be the principal motivators – not just the tax benefits – for any changes in IP location.

Examples include the recent codification of the economic substance doctrine under US tax law, with one senator specifically mentioning a ‘gimmick’ of shifting IP rights to a shell company without personnel or operations.

The EU is also pushing for codification and standardisation of the General Anti-Abuse Rule so it can be applied on a more consistent and broader basis to ‘aggressive’ tax schemes lacking business or economic motivations.

Sustainable IP Tax Planning

And The Impact Of New Rules

Staying Competitive

Incorporating Beneficial Foreign Intangible Property Structures into Tax Planning

To stay competitive, many multinational companies are looking at restructuring as a means of lowering taxes paid on income derived from intangible property (IP).

Sustainable IP tax planning will need to be able to withstand the impact of these new rules. In practical terms, this means IP tax planning should be increasingly aligned with management and economic activities – particularly as it relates to the IP profits.

This dovetails nicely with most national economic policies. Even if mere rhetoric, almost all countries at least acknowledge that attracting innovation, as well as related IP rights, talent and investment, to their jurisdiction is key to future growth. Many countries offer various tax incentives in the hopes of attracting IP and the associated profits, jobs and capital. The EU’s Lisbon Strategy for a knowledge-based economy has been the fundamental policy driver for the current batch of EU IP boxes.

National Economic Policies

In future, there appears to be potential alignment whereby low-taxed IP and related activities can harmoniously coincide in the same country. This implies IP tax planning needs to be linked to other factors building a business case for moving IP to a specific country.

Factors that will be increasingly relevant include a stable and flexible legal framework and the ability to attract key talent, such as executives, engineers and developers, through incentives such as the personal tax rate, availability of schools and quality of life. Additionally, a country’s infrastructure and the cost of running technical facilities and operations may need to be considered. In the case of R&D activities, the question is whether the country already has a critical mass of brainpower and talent or at least the legal flexibility to quickly migrate them.

Eu Locations For IP

Corporate Tax Planning

A sample of top EU locations (about half of the 26 EU member states have an IP box) for IP corporate tax planning, and these other increasingly important ‘business case’ factors, are summarised below.

The Netherlands

The Netherlands deserves credit for establishing the first patent box back in 2007. Currently, the Dutch ‘Innovation Box’ provides for an effective Dutch tax rate of approximately 5 per cent for either patents or IP derived from innovation. For the latter to apply, the Dutch company must obtain an R&D grant and, critically, the 5 per cent rate should only apply to the extent that the IP profits are further developed through identifiable R&D activities (via transfer-pricing study).

In practice, this can result in only a portion of total IP profits benefiting from the reduced rate.

Nonetheless, the Innovation Box can still be advantageous, especially if EU member states are already the location of actual R&D activities.

The Dutch expat regime allows key personnel to be temporarily transferred to the Netherlands and benefit from an approximate 36 per cent effective income tax rate (the normal rate is over 50 per cent). English is also a widely spoken second language in the Netherlands, while the country boasts a number of highly respected universities and research centres.

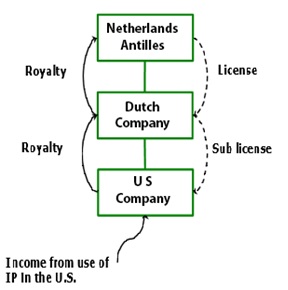

EXAMPLE

Conducting financing regulations would deny treaty benefits

![]()

Luxembourg

Despite its small size, Luxembourg has used its tax and legal flexibility to make a big impact in IP tax planning – particularly as regards information technology, e-commerce and biotechnology.

Many internet giants, such as Amazon and eBay, already have personnel and operations there.

Luxembourg has heavily invested in its high-tech infrastructure (with high rankings in a number of key ICT operational criteria) and there is already a sizeable pool of high-tech expat talent. Its IP box regime provides an effective tax rate of 5.8 per cent, with a relatively broad range of IP rights, including patents, software copyrights, trademarks, designs, models and domain names (although know-how, trade secrets and other key IP types are still excluded).

The government is active in attracting IP-related operations and talent.

Also, IP tax planning using more conventional methods (besides the IP box) can still result in an efficient tax rate, and this can be combined with a strong business case. The new coalition government recently announced a bold reform package, including further measures to attract innovation and IP, such as updating the IP box regime.

Malta

Malta is also worth mentioning. The Malta patent or copyright box can result in a zero effective tax rate – the lowest among common IP location candidates in the EU.

However, Malta’s weak spots might be substance and infrastructure (personnel, functions, facilities, etc), which will certainly become increasingly important for sustained IP tax planning into the future.

Ireland

Ireland has attracted a large amount of IP from a variety of industries, including ICT, e-commerce and biotechnology. This is due partly to its 12.5 per cent corporate tax rate, 25 per cent R&D credit system, and IP tax regime (a wide range of IP, including patents, copyrights, marketing intangibles and know-how, and a related capital allowance of 15 years or the economic life of the IP).

As for business case, the Irish Industrial Development Agency has the most active promotional offices among its EU counterparts, including an office in the heart of Silicon Valley. Ireland can be an easy sell for US MNCs, given its large English-speaking population, relatively low costs of labour, and similar, flexible common-law legal system. However, the luck of the Irish might be wearing thin. With its national debt far above 100 per cent of GDP, Ireland is also attracting a lot of attention in terms of anti-tax avoidance, both in the EU (there is pressure for Irish tax reform in light of the country’s bail-outs) and US Congress.

Ireland has already changed its domestic law under pressure from the US in an attempt to shut down one loophole often used in IP tax planning (so-called ‘stateless’ non-Irish resident companies).

Double Irish Arrangement

The double Irish arrangement is a tax avoidance strategy that some multinational corporations use to lower their corporate tax liability. The strategy uses payments between related entities in a corporate structure to shift income from a higher-tax country to a lower-tax country. It relies on the fact that Irish tax law does not include US transfer pricing rules. Specifically, Ireland has territorial taxation, and hence does not levy taxes on income booked in subsidiaries of Irish companies that are outside the state.

The double Irish tax structure was pioneered in the late 1980s by companies such as Apple Inc. However, various measures intended to counter such arrangements have been passed in Ireland as early as 2010. In 2013, the Irish government announced that companies which incorporate in Ireland must also be tax resident there. This counter-measure is proposed to take effect in January 2015.

Typically, the company arranges for the rights to exploit intellectual property outside the United States to be owned by an offshore company. This is achieved by entering into a cost sharing agreement between the US parent and the offshore company, written strictly in terms of US transfer pricing rules. The offshore company continues to receive all of the profits from exploitation of the rights outside the US, but without paying US tax on the profits unless and until they are remitted to the US.

It is called double Irish because it requires two Irish companies to complete the structure. One of these companies is tax resident in a tax haven, such as the Cayman Islands or Bermuda. Irish tax law currently provides that a company is tax resident where its central management and control is located, not where it is incorporated, so that it is possible for the first Irish company not to be tax resident in Ireland. This company is the offshore entity which owns the valuable non US rights that are then licensed to a second Irish company (and this one is tax resident in Ireland) in return for substantial royalties or other fees. The second Irish company receives income from the use of the asset in countries outside the US, but its taxable profits are low because the royalties or fees paid to the first Irish company are tax-deductible expenses. The remaining profits are taxed at the Irish rate of 12.5%.

For companies whose ultimate ownership is located in the United States, the payments between the two related Irish companies might be non-tax-deferrable and subject to current taxation as Subpart F income under the Internal Revenue Service's Controlled Foreign Corporation regulations if the structure is not set up properly. This is avoided by organizing the second Irish company as a fully owned subsidiary of the first Irish company resident in the tax haven, and then making an entity classification election for the second Irish company to be disregarded as a separate entity from its owner, the first Irish company. The payments between the two Irish companies are then ignored for US tax purposes.

Dutch Sandwich

Example of a double Irish with a Dutch sandwich:

1. An advertiser pays for an ad in Germany.

2. The ad agency sends money to its subsidiary in Ireland, which holds the intellectual property (IP).

3. Tax payable in Ireland is 12.5 percent, but the Irish company pays a royalty to a Dutch subsidiary, for which it gets an Irish tax deduction.

4. The Dutch company pays the money to yet another subsidiary in Ireland, with no withholding tax on inter-EU transactions.

5. The last subsidiary, although it is in Ireland, pays no tax because it is controlled outside of Ireland, in Bermuda or another tax haven.

Ireland does not levy withholding tax on certain receipts from European Union member States. Revenues from sales of the products shipped by the second Irish company (the second in the double Irish) are first booked by a shell company in the Netherlands, taking advantage of generous tax laws there. Overcoming the Irish tax system, the remaining profits are transferred directly to Cayman Islands or Bermuda. This entire scheme is referred to as the "Dutch sandwich". The Irish authorities never see the full revenues and hence cannot tax them, even at the low Irish corporate tax rates.

However, companies such as Google, Oracle and FedEx are declaring fewer of their ongoing offshore subsidiaries in their public financial filings, which has the effect of reducing visibility of entities declared in known tax havens.

Major companies known to employ the double Irish strategy are:

Abbott Laboratories, Adobe Systems, Apple Inc., Eli Lilly and Company, Facebook, Forest Laboratories, General Electric, Google, IBM, Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft, Oracle Corp., Pfizer Inc., Starbucks. Yahoo!

Content supplied by TBA & Associates